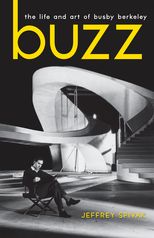

Buzz: The Life and Art of Busby Berkeley

Buzz: The Life and Art of Busby Berkeley

Contents

Cite

Abstract

Buzz decided to take an ambitious cross-country automobile trip with his mother. They would end up in New York, see old friends and colleagues, and take in a Broadway show or two. In April, Claire James instructed her lawyer to cancel the divorce action she had filed just two months before and sought an annulment at a later date. That same month, Buzz went to work for 20th Century Fox after they made an offer to MGM to “borrow him” for a one-picture deal. In early June, two months after filming began on The Gang's All Here, after the annulment was granted, she married twenty-four-year-old Lt. Ray Dorsey. In July, Jack Warner was back in Buzz's life, after negotiating a deal with MGM that included Joan Crawford.

Buzz requested a respite. He hadn’t taken a real vacation in years. He wedged in his weddings and his honeymoons whenever there was a free day or two in his schedule. His work on Girl Crazy ended far too precipitously, and his marriage was no longer tenable, so Buzz found himself with enough free time for a holiday. Louis B. Mayer, knowing full well the histrionics that had occurred between Arthur Freed, Roger Edens, and Buzz, gave him a month off. He decided to take an ambitious cross-country automobile trip with Mother. They would wind up in New York, see old friends and colleagues, and take in a Broadway show or two. Buzz might even do a little unpaid scouting for the next Berkeley girl.

Buzz and Mother rode in a limousine chaperoned by a man identified as “Gene.” They wheeled through Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas as Gertrude took in the sights from the right side of the backseat. In Oklahoma, a deep dip in the road caused the vehicle to bounce severely, forcing Gertrude off her seat and onto the limo’s hard floor. She was in pain, and her son brought her to the closest Oklahoma hospital he could find. Gertrude had torn the ligaments in one leg and needed a week’s hospitalization. Buzz was fraught with anxiety and need. He called Etta Judd and asked his kindly friend to come to the hospital and assist him with his mother, and she did so without a qualm. Though the automobile part of the trip was now canceled (Buzz asked Gene to return to Los Angeles), they planned to travel to New York by train. Gertrude looked at real estate advertisements during her convalescence. With her spendthrift son’s future in mind, she found a house in Oklahoma City and a cattle ranch in Shawnee on the market for a steal. Before Buzz and Gertrude boarded a train to points east, he had purchased the properties in his mother’s name per her request. The ride to New York could not have been comfortable for Gertrude. She was carried onto the train by stretcher (the second Berkeley to make such a public appearance). Approaching eighty, Gertrude was now permanently wheelchair bound. When the two arrived at their destination, the dutiful son kept at his mother’s side around the clock. During a day trip to Dover, New Hampshire, Buzz and Gertrude revisited the twenty-four-room mansion she loved. When they returned to California, one of the first things Buzz did was install wheelchair ramps in the Adams Street mansion.

In April, Claire James instructed her lawyer to cancel the divorce action she had filed just two months before. She told reporters that despite the cancellation, “there’s no reconciliation in sight. Just say I’m canceling it for the time being. I may have something to announce later.” Buzz said it was news to him that his wife’s suit had been withdrawn. His ignorance of the postponement could explain why he was seen with a San Francisco showgirl named Sally Wickman around this time. He and Sally were also seen at Slapsy Maxie’s. Columnist Dorothy Kilgallen said Buzz was “daffy” about Ms. Wickman, but neither the romance nor the showgirl’s career advanced very far.

That same month, Buzz went to work for 20th Century Fox after they made an offer to MGM to “borrow him” for a one-picture deal. The studio was not selfish with Berkeley (certainly not in the way Warner Brothers had been) once the Girl Crazy fiasco had played out. For Buzz, it was a chance to work again under studio chief Darryl F. Zanuck, his mentor and champion in his early Warner Brothers films. The picture’s working title was “The Girls He Left Behind,” and it was intended as Fox’s Christmas release of 1943. It was a wartime Technicolor home-front musical filled with specialty acts, spirited songs, and outrageous dance numbers. Its subject was certainly within Buzz’s artistic means and temperament. Composer Harry Warren (who hadn’t worked with Buzz since Garden of the Moon) was to collaborate with lyricist Mack Gordon, but by the time Buzz became attached to the film, Gordon had left the project and Leo Robin was assigned the lyrics.

America’s entry into World War II, following the 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, signaled an end to Hollywood’s profitable relationships with the Far East markets. At Fox, their continental and Japan-based operations were shut down. The studio looked to other markets for film distribution and found the Latin American countries of South America very receptive. With films such as Down Argentine Way, Week-end in Havana, and That Night in Rio, Fox cemented itself as the studio most willing to cater to this emerging market. A number of other factors contributed to the prevalence of Latin-themed films, namely FDR’s “Good Neighbor Policy,” North and South America’s hemispheric partnership against fascism, and the Office of Coordination of Inter-American Affairs, which had its own motion picture division. Even the Hays office appointed an expert in Latin America, but there was another factor besides the political that helped support this new emerging market; the songs and dances south of the border were extremely popular with American moviegoers. Buzz capitalized on the craze with the “Do the La Conga” number in Strike up the Band, but it was 20th Century Fox, above all other studios, that reaped the greatest rewards from its Latin-themed pictures in the early and mid-1940s.

The Gang’s All Here, as the film was now officially known, began production in April. Its cast included Fox’s contracted “ambassador” to the Spanish world, Carmen Miranda (who, by this time, had a couple of successful Fox musicals under her belt); Alice Faye, the contralto-voiced singer/actress who previously starred with Miranda; Charlotte Greenwood (working again with Buzz some twelve years after Palmy Days and Flying High); and radio host Phil Baker. Strong supporting character actors included Eugene Pallette and Edward Everett Horton as wealthy businessmen friends. Linda Darnell was to play Horton’s daughter, but her involvement in the film didn’t last long. A sprained ankle during rehearsals (Darnell had plans to dance for the first time in The Gang’s All Here) kept her sidelined. After her recovery, she eloped with famed cinematographer J. Peverell Marley and asked Fox for an indefinite leave of absence. Actress Sheila Ryan, under contract to Fox with about twenty film roles to date, replaced her.

Buzz learned that Darryl Zanuck would not be overseeing the production. Fox’s studio head was in Europe on behalf of the war effort, leaving the chore to William LeBaron. LeBaron was a producer and songwriter who had worked at other studios before coming to Fox. Under Zanuck, he set up an independent unit at the studio, mostly making musicals. He and Buzz got along well at first, but the relationship was soon strained as the showman in Berkeley wouldn’t yield to the budget-trimming mandates of LeBaron (who, in turn, was forced to trim expenses due to the demands of the War Production Board, which sought cost cutting in all aspects of businesses during the war). In spite of the producer/director set-tos that took place during shooting, the film turned out to be an outrageously conceived work of art, blending with subtlety the politics of alliances while overtly disarming the viewing public with surrealism and spectacle.

The motivations of Claire James were unknown to those who worked with Buzz. Claire was often seen driving him home from the studio, “despite reports that they’re kaput.” In early June (two months after filming began on The Gang’s All Here), she filed suit to annul the marriage. She said that at their ceremony, Buzz had expressed his willingness to be her husband, but that afterward he had refused to live with her and had been a husband in name only. The final straw came when Claire went to visit Buzz on his set. He had her thrown off by her own father, who worked as a studio watchman.

By midmonth she had received her annulment; she had requested no money from Buzz. Claire’s cryptic remark to reporters in April (“I may have something to announce later”) came true less than one week after the annulment. Her photograph was featured on the syndicated wedding announcements page with the news that she was to become the bride of twenty-four-year-old Lt. Ray Dorsey as soon as he could get leave from his duties at March Field, California. Evidently, the lieutenant received his leave sooner than expected; he and Claire were married before the month was over.

The Gang’s All Here begins in motion, and for the first seven-plus minutes it thrills, disorients, and confounds the nature of space and place through purely cinematic means. Far in the upper left corner of the screen, we hear and see a man (Aloysio De Oliveira) sing the popular song “Brazil.” In a shot reminiscent of the opening moments of “Lullaby of Broadway,” Berkeley’s movable camera slowly closes in on the singer (whose face is half-hidden), and just as quickly moves away from him as a new, undefined image appears: a group of thin strips of bamboo, angled left, giving way to the marking on the docked ship SS Brazil. The camera flies weightlessly as it follows embarking passengers and the ship’s crew and cargo, when, in a clever transitional shot (a roped fruit basket blending into a fruit-filled hat), Carmen Miranda is introduced. A few seconds later Buzz allows the audience to regain its bearings by dollying back, revealing the locale as a nightclub with an audience and a small stage. As in previous films, his flights of fancy disregarded any physical limitations imposed by reality. Here, the stage is quite small, making the opening number a supreme example of the director’s art meeting visual trickery. Miranda yields her singing to the audience as the heretofore unknown showgirls are seen, one at a time, in close-up. The camera moves from one face to the next accompanied in the shot by small musical instruments used in the show. The last of the showgirls (played by Alice Faye) remains unidentified until the number ends, and we’re finally introduced to the film’s supporting players.

The “book” of The Gang’s All Here is fairly simplistic, as insubstantial as the Mickey/Judy “Babes” pictures. On the record, Buzz had mentioned his disinterest in or outright disdain for the expository passages of his musicals. Here, especially, the dialogue sequences are generally insignificant relative to the total sheen that Buzz, the preeminent showman, provides. Dialogue-driven scenes are played mostly in a fast, clipped manner where one sentence has barely enough breathing room before a reply is uttered. It’s an interesting way to direct his actors (one thinks of Buzz’s similarly rapid-fire Fast and Furious), as if he hadn’t the patience to slowly maneuver nonmusical moments. In light of the fact that Buzz almost always directed a picture’s musical numbers first and concentrated on the story afterward, it isn’t a stretch to imagine him picking up the dialogue’s tempo in an effort to wrap the picture on time and under budget.

Of the half-dozen songs in The Gang’s All Here, certainly the one most playful to both ear and eye is “The Lady in the Tutti Frutti Hat,” written especially for Carmen Miranda per Buzz’s request to Harry Warren and Leo Robin. It has all the earmarks of classic Berkeley: a self-contained story without reference to the “book”; sets that can exist only on an expansive soundstage; and unworldly (if not unwieldy) large props unfamiliar in scope to anything found in nature. As the number begins, an organ grinder and monkey make their way toward the stage, where we see a number of ersatz banana trees, each with its own monkey. We’re carried along on Buzz’s buoyant camera as it surveys an imaginative set evoking a South Seas atoll. On this idyllic islet reside dozens of Buzz’s beauties, all sporting yellow kerchiefs, black, flaring midriff tops, and canary yellow short shorts cut high above the thigh. There they dally and rest under imaginary sunshine, their legs bent in suggestive poses. Suddenly they hear someone approach, which causes them to line up in two rows, single file, and wave to the visitor. This action keeps Buzz’s camera moving up to the outrageous image of the Brazilian Bombshell herself being pulled on a banana cart by two gold-painted oxen, supported by two muscle-bound manservants and a half-dozen musicians! “The Lady in the Tutti Frutti Hat” immediately establishes itself as a self-affirming and presence-establishing number for Miranda. From the first line, in which she asks naively, “I wonder why does everybody look at me?” and follows up later with an interesting declarative: “Some people say I dress too gay, but ev’ry day I feel so gay, and when I’m gay I dress that way, is something wrong with that?” the song revels in the excess of her character, giving Buzz ample opportunity for unbridled impressionistic creativity. The action shifts to the girls formed in a circle holding portable xylophones made of small bananas while Carmen pretends to play. The scene blends into shots of the girls’ legs and feet as they line up in formation, now holding five-foot plastic (and unashamedly phallic) bananas over their heads. This allowed Buzz to pursue the folly of his imagination as his dancers raise and lower their bananas in patterned sequences, while he overcranks the camera for a slow motion effect. Buzz’s camera rises, dips, and tilts in glorious abandon like a drunkard on ice. The girls eventually return to their original positions, and the camera pulls away to reveal a dozen organ grinders with their monkeys. Buzz tracks past the last one to reveal Miranda again in a surrealistic final shot. As she finishes her number, the camera pulls back, revealing the allusion that her banana hat is the largest one in the world, extending to infinity (thanks to the terrific matte painting and production design of James Basevi and Joseph C. Wright). Buzz surreptitiously winks to the audience as he closes the song and the stage curtains drop.

Buzz boasted of his one-take acumen when the camera rolled, but it seems he forgot about the problems he encountered in the “Tutti Frutti” number. Cinematographer Edward Cronjager was a well-respected professional, and by 1943 he had photographed some one hundred pictures, including Western Union for the demanding Fritz Lang and Heaven Can Wait for Ernst Lubitsch. He also worked with Buzz back in 1932 for the numbers in Bird of Paradise. In all those films, he couldn’t recall working on a picture that demanded he ride the boom as aggressively as he did in The Gang’s All Here. That aggressiveness almost caused a serious accident. Reporter Harold Heffernan of the Detroit News was on the set during the “Tutti Frutti” number and noticed how happy Buzz was riding shotgun on the boom as Cronjager manned the camera. All the while the camera boom darted and swooped and raised and tilted mere inches past the faces of the lovely Berkeley girls. In one near-tragic take (what Heffernan called “Berkeley’s frantic gesticulations”), the boom overshot its mark and came uncomfortably close to Carmen Miranda’s head, knocking off the top layers of flowers and fruit leaves from her hat. As Buzz and Cronjager reset their position at the top of the stage, Miranda let off steam to the reporter saying, “Dat man ees crazy.” She went on a bit louder so Buzz could hear: “What you theenk you are anyhow, a head hunter? If you want to keel me why you don’ use a gun?” According to Heffernan, Buzz pleaded nicely with Carmen from his position high above her. “Hookay. Thees time make with the careful! Knock one banana off my head and I will make of you de flat pancake,” threatened the malapropist. According to another reporter visiting the set when “The Lady in the Tutti Frutti Hat” was filming, Buzz was up on the boom and yelling at the dancers below, his rasping voice pleading, “Girls, girls, can’t you see?” He explained his method to the reporter: “We’ve got a camera that can go anywhere. Why not use it? Sure a theater audience couldn’t look down on a stage full of dancers, but that’s no sign it wouldn’t like to. If the camera can let ’em why not?” After a day’s filming, the more amiable director took his girls to the projection room to watch the dailies. “They’re usually surprised,” said Buzz, who, according to the report, seemed anything but.

Buzz again displayed a director’s maturation in his sensitive and restrained touch with the two main numbers sung by Alice Faye. The melodic “A Journey to a Star” is repeated throughout the picture, but in its first incarnation it’s sung as an audition of sorts on board a ferryboat with the moon as its sole light source. Alice “cues” an unseen orchestra (the film is all about the suspension of disbelief) and sings to B-actor James Ellison while Buzz holds a steady shot of his principals bathed in beautiful, artificial moonlight. At one point during the song’s reprise, both actors turn to face the water, leaving their backs to the camera (and audience) in a complete disregard for propriety (one wonders how the MGM brass would have reacted). Yet Buzz made the right directorial decision, keeping the number fresh by the simple act of pivoting his leads within their confined space. (Such is the unimportance of narrative that, although James Ellison’s role is the romantic lead, he’s billed ninth in the credits.) “No Love, No Nothing” is sung by Faye onstage at the club New Yorker using the show’s rehearsal time as a pretense for the performance. In the number, she plays a woman missing her man who is fighting in the war. She meanders about her small apartment; runs to the door in vain when someone approaches; lovingly picks up her man’s pipe and his slippers; and in tears she turns off her lamp, finishing the song as a sliver of light illuminates her sadness. The number (as meant for the live audience) is an undisguised metaphor to the ongoing story line (the James Ellison character has gone overseas, leaving Alice bereft). Buzz accomplishes a wonderful sleight of hand. At the song’s conclusion, not only is its veiled reference to the narrative made obvious, it becomes warmed with emotion, leaving the reason for performing the number in the first place (it was a dress rehearsal) completely forgotten.

Not since his films at Warner Brothers had the stacking approach to Berkeley’s musical numbers been given. The ganging up of big production numbers, as already mentioned, left only those numbers in memory while a film’s preceding one hundred minutes were all but dismissed. In The Gang’s All Here, the over-the-top combination of Berkeley’s fertile imagination painted with three-strip Technicolor swatches kept even the early numbers (including the bravura opening) still vivid in recollection. The final ten minutes of the film is a type of number stacking that leads to an explosively surreal climax in which the kaleidoscopic and expressionistic vision of Busby Berkeley is fully realized.

As originally designed, Buzz regarded the finale with little enthusiasm. It didn’t seem big enough. It wasn’t “spectacular.” Production notes point to a patriotic ending featuring a military wedding (James Ellison and Alice Faye), costumed in red, white, and blue. How this potentially bombastic number (military marching bands, explosions, and song; all de rigueur for a Berkeley ending) was deferred for the visual splendor of the avant-garde finale isn’t known. But the authorial stamp of The Gang’s All Here is Buzz’s in the two credits given him (“Dances created and directed by,” and the full director’s credit), so his final word for the final number was final.

The film ties up all its narrative strings as the action turns to a war-bond garden party to be given outdoors on the well-manicured grounds of the Edward Everett Horton character’s Westchester County estate. The finale begins with a close-up of the invitation, a five-thousanddollar bill strategically placed below it (the price of an invitee’s war-bond purchase) and two polished fingernails holding both. Chopin’s Nocturne plays as the Berkeley camera surveys the grounds, stopping at a tastefully nude statue as the action and tempo change. A pink-lit, circular, colored waterfall drops to reveal Benny Goodman and His Orchestra as the scene shifts in focus. (Buzz’s use of the waterfall as a transitional device is highly effective in a reverse-curtain way. Here the waterfall descends as a sequence begins in contrast to a theater’s curtains that rise.) “Paducah” (“If you wanna, you can rhyme it with bazooka”) is Benny Goodman’s at the start, as Buzz’s boom follows him from one musician to the next up a U-shaped bandstand with Goodman at the center (instead of out front) of his band. It should be mentioned that, in this elegant outdoor setting, over his left shoulder is the earthly impossibility of a grand chandelier! What is it hanging from and who is holding it? Is it tethered to the moon? But these are retrospective musings for the literalist only, as Buzz and his production designers forswore physical reality from the film’s first frame. Carmen Miranda takes over the vocals, and the number shifts to a dance with Tony De Marco, once again, playing to the South American market. The vertical waters, now tinged blue, drop to reveal Berkeley’s girls positioned in ascending order for a reprise of “A Journey to a Star.” A close-up of each face passes the camera, resting on Alice Faye. As she finishes, Buzz’s camera-in-motion turns left to a pink-shaded water curtain. As it drops, we watch De Marco and Sheila Ryan in a pas de deux. Their number ends, and the camera repeats it movement, closing on Alice Faye as she finishes while a blue fountain rises. A small pause is taken to wind up the narrative (the course of true love is set on its proper path and wrong suppositions are righted—as if Buzz [and we] cared a hoot) before the grandest of grand finales unfolds.

The circle is the shape on which “The Polka Dot Polka” number is designed. In the cinematic world of Busby Berkeley, an object or a geometrical pattern is given uncommon significance as seen as far back as the Gold Diggers films. Here, the song’s title (lyrics be damned) enmeshes with the director’s vision of circularity. The number begins with two dozen girls dressed in polka-dot outfits dancing with boys wearing polka-dotted bow ties. Alice Faye (in a dress of blue polka dots) walks in gracefully, singing as she maneuvers between the children. “The Polka Dot lives on,” sings Alice, and from this point to the end of the film, any relation to spatial reality is strictly coincidental.

A shot of a girl’s hand and forearm with interlaced circles amid a white sleeve transforms to a larger version of the arm as the red circles change to round, red neon tubes and position themselves in a long string, barely touching. The neon tubes then drop into the waiting arms of the Berkeley girls (dressed in outlandish full-body costumes reminiscent of those in the Flash Gordon serials). The girls, now spread out on a five-tiered set, take the neon circles and rotate them (the ubiquitous Berkeley shadow of a dancer doing the same moves can be seen in the background). The neon has been be replaced by flat circles that are rolled to the floor. In a terrific shot that was projected in reverse, the circles lift off the ground into the arms of the girls. They, in turn, pivot around and send the flat circles to the girls in the lower tier. A large gold circle fills the frame as a transitional device, and now Alice Faye can be seen in a high shot, swirling in a large blue dress. The image changes again to a full kaleidoscopic view of her in eight mirrored representations. At this point, thirteen years in development, the Berkeley aesthetic has reached the apex of maturation in the loftiest cinematic affirmation of his singular talent. Buzz’s dominating acumen is presented in arresting, color-flushed images supplemented by an ascending musical score that blends to a fever pitch of unrestrained frenzy as the kaleidoscope turns and turns, every two seconds, at every manifestation a repainting of the screen with hypnotizing hues until the number ends breathtakingly and satisfyingly in complete and total exhaustiveness. With a start and a laugh, the number abruptly transitions to a circular-framed shot of Eugene Pallette’s disembodied head zooming toward the camera as he warbles the first line of “A Journey to a Star.” Joining him, one by one, are the rest of the cast, each filmed as a headshot against a different-colored background until the whole gang (including the Berkeley girls) is seen in a single shot with heads in (and bordering) the frame (a fine special effect for its day). The pink-tinged water fountain rises for its final time and gives way to the end card, which, in its lower right corner, reads: “For Victory, U.S. War Bonds and Stamps. Buy yours in this theatre.” The not-so-subtle solicitation worked (that is, you in your seats can help our servicemen just as the happy singing folks you witnessed did), and audiences of the day responded enthusiastically.

Buzz worked longer on “The Polka Dot Polka” finale than any number he had done. At first, he couldn’t envision the closing sequence. One day, by chance, he stared intently at a topaz ring he had recently purchased for Gertrude. The stone acted like a prism, bending the light in interesting ways. “If only I could shoot through this,” mused Buzz. His secretary, Helen McSweeney, came up with the idea of a kaleidoscope. She said she knew of a kid who had one nearby. Buzz looked into the toy and began a “mental victory dance.” Always the idea man, he came up with a contraption costing roughly eight thousand dollars. It was a vertical shaft with two sides supporting hinged mirrors at 45-degree angles from each other. Buzz and his boom were placed high above the device, looking downward while the stage revolved like a turntable. As it spun, a section of the moving floor came into camera range and the mirrors reflected the multiple images of whatever was on the stage. So Buzz placed Alice Faye, his girls, and the color combination that suited his fancy, and created an amazing collage in the final edit.

In July, Jack Warner was back in Buzz’s life. Although still employed at MGM, Buzz had heard word from Warner Brothers that they were again interested in his services if he could somehow be released from his contract. MGM packaged Buzz with studio stalwart Joan Crawford, and made a double deal with Warner Brothers. They could have him if Joan was included. Jack promised Buzz a five-year contract at better terms than what he was getting. “He’s back on the Warner lot to stay,” announced Louella Parsons.

Lorraine Breacher, a native Chicagoan, was an extra in The Gang’s All Here. Buzz found her attractive, and soon she was seen on his arm. With the rapidity of the grand emotional gestures that had plagued Buzz, he placed a “sparkler” on Lorraine’s proper finger. On August 10, it was announced they intend to wed in 1944. There was a twenty-one-year age difference between them.

In September, Jack Warner learned that 20th Century Fox recently had ceased to pay Buzz for any additional work. There was a small problem. Buzz needed to return to Fox for a day’s pickup shots for The Gang’s All Here. Jack gave his OK, but he made sure that Fox paid the studio for the day. The next month, producer Alex Gottlieb complained to Jack that Buzz had requested a couple of days off. Buzz flew to Chicago with Lorraine to see her ill mother. In a memo to Warner, Gottlieb wrote, “I felt this was entirely out of line.” Girl Crazy was finally released in November, the same month that Buzz learned of new IRS troubles. A $26,947 income tax lien had been filed against him on November 25.

Buzz was working on the budget for his next project, his first film at Warner Brothers as full director since They Made Me a Criminal. But things had changed in the four intervening years. One of these changes was Jack Warner’s temper regarding Buzz. Though famous directors basked in the public spotlight, they were often castigated in private. To the heads of the studios, directors were regarded as overhead. They were employees, subject to verbal assault from their bosses. When Buzz missed a scheduled budget meeting, Jack Warner, in a rage, fired off a memo stating that he had called Buzz and asked him why he hadn’t come to work. Buzz answered that the battery in his car would not start. Quote Jack: “I told him off plenty and he started to apologize and I then virtually insulted him. In case we need evidence against him in the future you can hold this on file as well as the trip to Chicago he made several weeks previous to today.”

In mid-December, initial work had begun at Warner Brothers on the tentatively titled “Judy Adjudicates,” set to star Faye Emerson and Dennis Morgan. Emerson was to replace the previously cast Jane Wyman, but ultimately Emerson was dropped in favor of Joan Leslie. Robert Alda was assigned Dennis Morgan’s lead role. The title was changed to Cinderella Jones, and it was announced as Busby Berkeley’s new picture at his “alma mater.” Things started off precipitously; two days before Christmas, Buzz threw a party at his Adams Street home. The host’s sobriety might have been at issue, for Buzz slipped on a piece of spaghetti on his kitchen floor and broke his right wrist. One of the guests, a doctor, rushed Buzz to his office and placed his arm in a plaster cast. Later, after the plaster hardened, a hole had to be cut out so that the face of his watch (which the doctor forgot to remove) would show through. It was a disappointed Busby Berkeley that never made it to the premiere of The Gang’s All Here, his magnum opus of art and audacity.

The Gang’s All Here opened Christmas 1943 at the Fox-owned Roxy Theatre in New York. Most of the reviews were positive with the exception of the one appearing in the New York Times, which noted a Freudian slant to Berkeley’s giant bananas: “But in the main, The Gang’s All Here is a series of lengthy and lavish production numbers all arranged by Busby Berkeley as if money was no object but titillation was. Mr. Berkeley has some sly notions under his busby. One or two of his dance spectacles seem to stem straight from Freud and, if interpreted, might bring a rosy blush to several cheeks in the Hays office.”

The American Motion Picture Arts and Sciences library offered no confirmation to the rumor that The Gang’s All Here was banned in Brazil because of the way the giant bananas were used in “The Lady in the Tutti Frutti Hat” number. The picture was approved for export to South American countries soon after its New York release.

Buzz convalesced as well as his short temper would allow (he was anything but a subdued patient). On December 30, with his arm in a sling, he “directed” his Cinderella Jones stars in a radio truncation of the film’s story. Douglas Drake, a new young actor in the cast, joined Robert Alda and Joan Leslie. During the radio play Drake made a tentative upraised gesture with his hand. Why he did it was a mystery (who would see it?), but evidently stage directions prompted him. Buzz didn’t like it a bit. In a voice that could be heard from every corner of the stage he yelled, “Drake! Stop raising your hand so high! The way you’re doing it looks like ‘Teacher, I want to go!’”